This article originate from my contributions to Energiris, a Belgian citizens’ cooperative committed to accelerating the energy transition. As part of our mission to inform and raise awareness among both co-owners and the general public, we regularly publish educational content on topics related to sustainable energy.

The original article was published in French and Dutch, reflecting the multilingual context of our cooperative. By sharing them here in English, I also wish to reflect my personal commitment to a more sustainable and better-informed society.

Originally published on the Energiris website – 26 July 2025

A founding concept: sustainable development

For several decades, the question of balancing economic growth, social progress and environmental preservation has been at the heart of global concerns. It was in this spirit that the concept of sustainable development was born, popularised by the Brundtland Report (1987): ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’.

This idea, simple in appearance, is the result of a collective journey and alarming observations made as early as the 1970s. The United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm in 1972 was the first to warn of the destructive effects of uncontrolled development linked to human activities on the planet. In the same year, the Club of Rome, in its report ‘The Limits to Growth’, highlighted the incompatibility of infinite economic growth with finite natural resources.

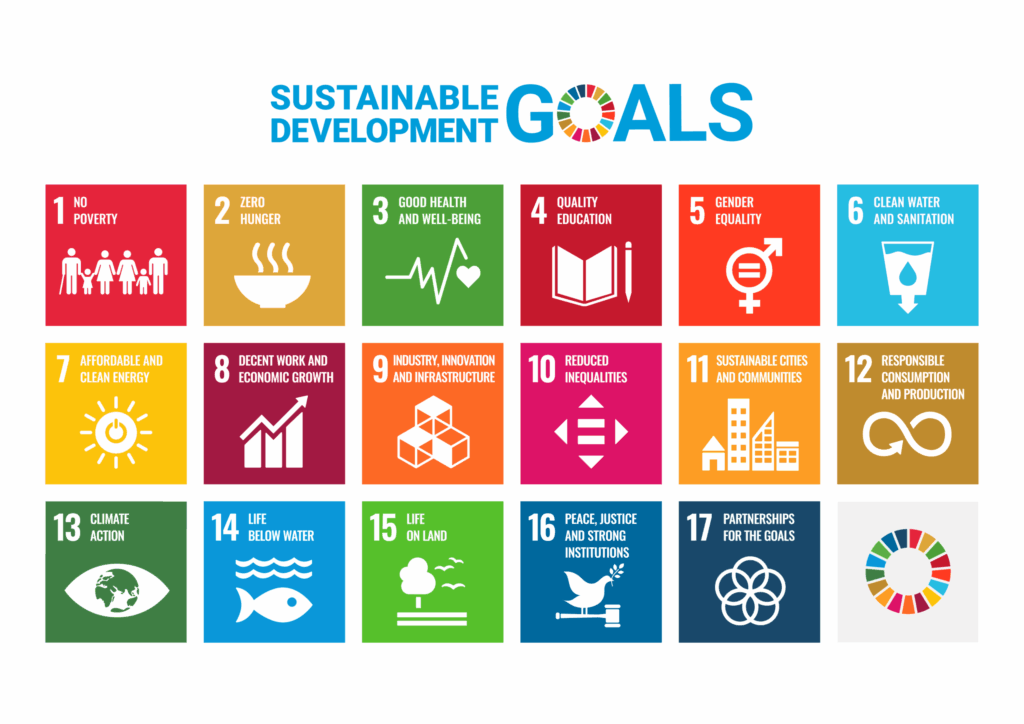

In 2015, this vision was translated into action with the adoption by the United Nations General Assembly of the 2030 Agenda and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These goals set out a global action plan to eradicate poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity for all by 2030.

Several of these goals are directly related to the themes of energy transition and climate action (SDG 7 – Affordable and clean energy, SDG 13 – Climate action), but also to equality, responsible consumption and governance (SDGs 11, 12, 16 and 17).

These SDGs provide a common direction that links local actions to global priorities.

Since then, this awareness has continued to grow through international agreements: the Montreal Protocol (1987) on the protection of the ozone layer, the Kyoto Protocol (1997) on greenhouse gas emissions, the Paris Agreement (COP21 in 2015), and more recently COP26 (Glasgow, 2021) and COP27 (Sharm el-Sheikh, 2022), which highlight the urgent need to take action on climate change.

One goal: to reconcile human well-being with respect for planetary boundaries

Sustainable development is not just about the environment: above all, it aims to ensure human well-being today and tomorrow. By protecting biodiversity, limiting air, water and soil pollution, and combating global warming, we are preserving the ‘environmental commons’ that make life possible: breathable air, clean water, fertile soil and resilient ecosystems.

Taking action for sustainable development means reducing health risks, protecting food security and access to vital resources for all, especially for the most vulnerable populations. It also means encouraging more modest and supportive lifestyles that promote equity between generations and between territories.

Energy transition: one of the concrete levers for transforming our models

Faced with this ambition, a central question arises: how can it be translated into concrete actions? One of the most concrete answers lies in energy transition, as one of the most visible levers for achieving sustainable development.

It refers to the gradual transformation of our energy production and consumption systems and involves moving from a system based on fossil fuels, which are high CO₂ emitters, to a model based on renewable energies and more efficient and sober consumption.

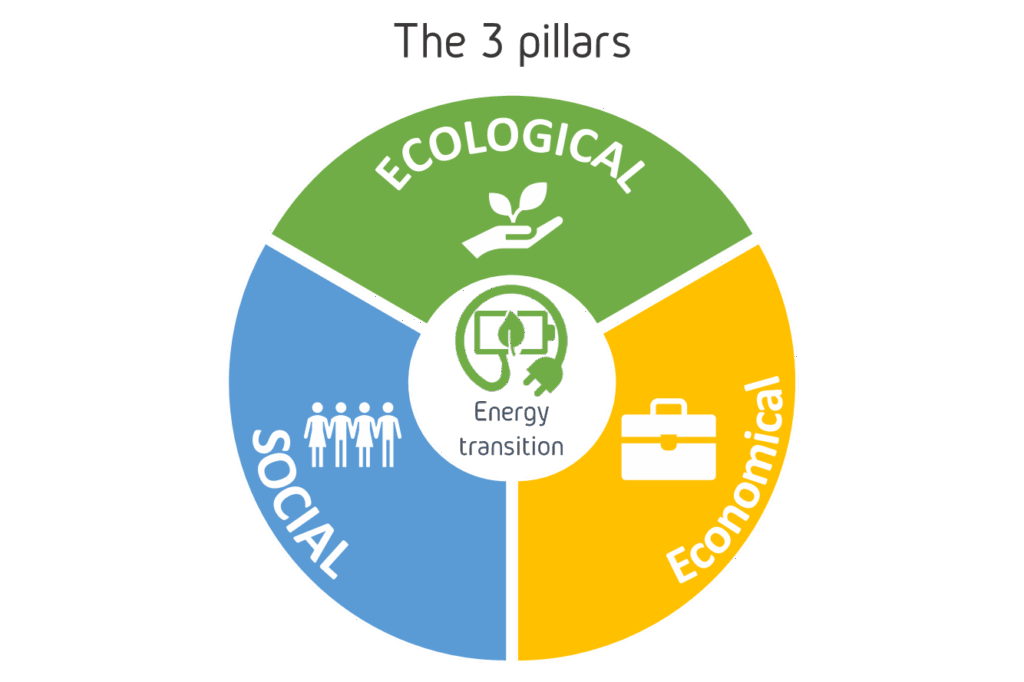

The energy transition is not just a technical process. It embodies the true implementation of sustainable development by acting jointly on its three fundamental pillars:

- Environmental: by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, it contributes directly to the fight against climate change;

- Economic: it promotes innovation, stimulates local employment and strengthens the energy autonomy of territories;

- Social: it enables democratic governance, involving citizens and generating concrete benefits at the local level.

But beyond the technological challenge, the energy transition invites us to fundamentally rethink our economic and social systems. It questions the organisation of our networks, the distribution of wealth, the way energy is governed and the strategic role of regions.

By promoting local production, focusing on energy efficiency and encouraging autonomy, it paves the way for more equitable, supportive and resilient models. It encourages everyone — citizens, businesses and public authorities — to adopt more responsible consumption practices, placing quality of life at the heart of priorities, rather than the mere accumulation of goods.

Alongside citizen engagement, businesses also have decisive levers at their disposal to drive the transition forward.

State institutions alone cannot bring about this transformation. It requires the mobilisation of civil society, and businesses also have a central role to play in this movement.

This is where Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) comes in, as a bridge between businesses and sustainable development. CSR refers to the voluntary integration by companies of social, environmental and economic concerns into their activities and interactions with their stakeholders (customers, employees, suppliers, local communities). According to the European Commission (2011): ‘CSR is the responsibility of companies for the effects they have on society.’

The commitment of companies to a CSR approach is a concrete contribution to the energy transition and the implementation of sustainable development in the economic world. A responsible company adopts best practices, such as:

- reducing its energy consumption;

- using renewable resources;

- limiting waste and polluting emissions;

- supporting regional development;

- protecting human rights and the well-being of its employees.

More than just an environmental approach, CSR embraces an integrated vision of the social, economic and ecological impacts of business activity. It translates into strong commitments: reducing carbon footprints, using clean energy, designing sustainable products, strengthening local roots, etc.

Some companies go even further, sourcing from citizen cooperatives, investing in low-carbon infrastructure or rethinking their business model to fully integrate energy issues.

CSR is thus becoming a strategic lever for transforming business models towards greater resilience, transparency and social justice, in perfect harmony with the objectives of the energy transition.

A virtuous circle for the planet and future generations

Ultimately, sustainable development, energy transition and CSR form a coherent whole:

- Sustainable development is the overall framework that sets the ambition.

- Energy transition is one of the major levers for achieving this ambition.

- CSR is the concrete tool that enables companies to actively contribute to this objective, alongside citizens and public authorities.

Everyone (citizens, businesses and local authorities) can thus play their part in a more efficient, more inclusive and more environmentally friendly model of society. Initiatives such as Energiris are a concrete illustration of this dynamic: clean energy, produced and controlled locally, for today and tomorrow.

Challenges and limitations: why it’s more complex than it seems

However, this model is not without its challenges. Despite progress, many companies still use the term CSR as a marketing argument without making any profound structural changes — this is sometimes referred to as greenwashing. The energy transition, for its part, is hampered by technical (storage, networks), financial (initial investment costs), political (will and consistency of strategies) and social (local acceptability, behavioural change) obstacles.

Some critics also point out that the concept of sustainable development often remains too vague to truly transform our lifestyles: it can be misused to justify projects that, in reality, perpetuate a growth model that is incompatible with planetary limits.

Beyond my role at Energiris, I place great importance on sharing knowledge. I have always considered education to be an essential tool for helping everyone better understand energy issues and the concrete solutions available to us. Sharing what I discover and making complex topics accessible to others is also my way of contributing to a fairer, more inclusive transition.

References

- World Commission on Environment and Development (1987). Our Common Future (Brundtland Report).

- Meadows, D.H. et al. (1972). The Limits to Growth. Club of Rome.

- United Nations (1972). Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment.

- United Nations (1987). Montreal Protocol.

- United Nations (1997). Kyoto Protocol.

- United Nations (2015). Paris Agreement (COP21).

- United Nations (2021, 2022). COP26 (Glasgow) and COP27 (Sharm el-Sheikh).

- European Commission (2011). A New EU Strategy for Corporate Social Responsibility.