This article originate from my contributions to Energiris, a Belgian citizens’ cooperative committed to accelerating the energy transition. As part of our mission to inform and raise awareness among both co-owners and the general public, we regularly publish educational content on topics related to sustainable energy.

The original article was published in French and Dutch, reflecting the multilingual context of our cooperative. By sharing them here in English, I also wish to reflect my personal commitment to a more sustainable and better-informed society.

Originally published on the Energiris website – 6 september 2025

What if our fields became the driving force behind the energy transition?

Faced with the climate emergency and pressure on agricultural land, an innovative solution is emerging: agrivoltaics. This concept makes it possible to produce solar electricity while continuing to farm the same plot of land. It’s a simple but powerful idea — especially if it is supported by citizens.

1. Introduction

1.1. Global context: climate emergency, energy transition and pressure on agricultural land.

In the face of the climate emergency, the energy transition aims to reduce CO₂ emissions while responding to growing pressure on agricultural land (Dupraz et al., 2011).

Faced with the challenges of energy transition and the preservation of agricultural land, agro-photovoltaics is emerging as an innovative solution. But what is it, and how can it transform the energy and agricultural landscape in Wallonia?

The fight against climate change requires a profound transformation of our energy production and consumption systems. In this context, renewable electricity production, and in particular photovoltaics, is expanding rapidly. However, this expansion poses a major challenge: limiting land artificialisation while ensuring energy supply.

Agrivoltaics, or agro-photovoltaics, appears to be an innovative solution for reconciling agricultural production and energy production on the same surface area. The concept was theorised by Goetzberger & Zastrow (1982) and was later tested in practice in Japan from the 2000s onwards. Today, this concept is enjoying renewed interest in Europe, particularly in France and Germany. In Belgium, several pilot projects are emerging, particularly in Wallonia, and are sparking debate about their relevance and impact.

However, this practice raises crucial issues: preservation of agricultural land, impact on biodiversity, risks of land speculation, but also opportunities for farmers in terms of additional income and energy independence.

This article examines the fundamentals of agrivoltaics, its multiple benefits, its legal framework in Belgium and Europe, and the criticisms levelled against it. Finally, we explore the conditions necessary for controlled development, particularly through the involvement of citizen cooperatives such as Energiris.

1.2. The issue: between promised synergies and land tensions.

Agrivoltaism, by combining agricultural production and energy production on the same surface area, raises complex issues of coexistence between different uses. While this approach promises multifunctional land use, it raises questions about the ability of territories to reconcile the imperatives of food sovereignty, energy transition and land justice.

In Belgium, where pressure on agricultural land is intensifying, agrivoltaics can become a strategic lever – or a factor of imbalance. The risks of agricultural land substitution, land grabbing by external actors, or fragmentation of rural landscapes are real. Conversely, synergies are possible: climate protection for crops, diversification of income, and local anchoring of energy production.

The central issue addressed in this article is therefore: how can the development of agrivoltaics in Belgium be regulated so that it represents a real opportunity—rather than a threat—for agriculture, local areas and citizens?

2. What is agrivoltaics?

2.1. Definition(s)

Agrivoltaism, also known as agro-photovoltaics or agrivoltaics, refers to the integration of photovoltaic panels on agricultural land with the aim of enabling the simultaneous use of the land for renewable electricity production and agricultural activity (Weselek et al., 2019). Unlike conventional photovoltaic installations, which can lead to soil artificialisation, agrivoltaics aims to achieve functional coexistence between the two uses, while maintaining the agricultural vocation of the land.

This concept is based on a logic of synergy: photovoltaic structures are designed to adapt to the needs of crops or livestock, while optimising solar capture. Agrivoltaic projects can thus contribute to the climate resilience of farms, the diversification of agricultural income, and the territorial energy transition.

2.2. History and development

Popularised in Japan in the 2000s with the first experiments in growing food crops under solar panels, the concept was theorised as early as 1981 by Goetzberger and Zastrow, then developed in Europe from the 2010s onwards thanks to the work of INRAE and Dupraz et al. (2011) , who demonstrated the agronomic and energy potential of this approach.

Since then, numerous pilot projects have been launched in France, Germany, Italy and, more recently, Belgium. Changes in the regulatory framework, particularly in France with the APER[1] law (2023), reflect a growing recognition of the agrivoltaic model as a lever for sustainable transition.

2.3. Types of systems

Agrivoltaic systems come in several technical configurations, depending on agronomic objectives, land constraints and climatic conditions:

- Fixed structures: raised static panels, suitable for field crops and pastures.

- Solar trackers: systems that can be adjusted to follow the sun’s path, allowing for better energy optimisation while modulating shade (Marrou et al., 2013).

- Solar greenhouses: integration of panels into the roofs of agricultural greenhouses, particularly suitable for horticulture and market gardening.

- Bifacial or vertical systems: panels that capture light on both sides, often used in meadows or mowing areas.

Each type has specific advantages in terms of energy yield, agronomic compatibility and installation cost.

2.4. Agronomic and technical principles

The installation of solar panels on agricultural land modifies several agronomic and microclimatic parameters:

- Partial shading: the panels create a shaded area that can reduce crop water stress, protect against adverse weather conditions (hail, frost, heat waves), and improve animal welfare in pastures (Barron-Gafford et al., 2019).

- Altered microclimate: the temperature under the panels is generally more stable, humidity is better preserved, and evapotranspiration is reduced, which can improve crop resilience.

- Optimised irrigation: the structures can facilitate water management, in particular through the integration of sensors or rainwater harvesting systems.

- Effects on plant growth: depending on the species grown and the level of shade, yields can be maintained or even improved, provided that the design is appropriate.

These effects vary depending on the crops, soil and climate conditions, and the density of the installations. Rigorous design is therefore essential to ensure compatibility between agricultural and energy production.

3. The benefits of agrivoltaics

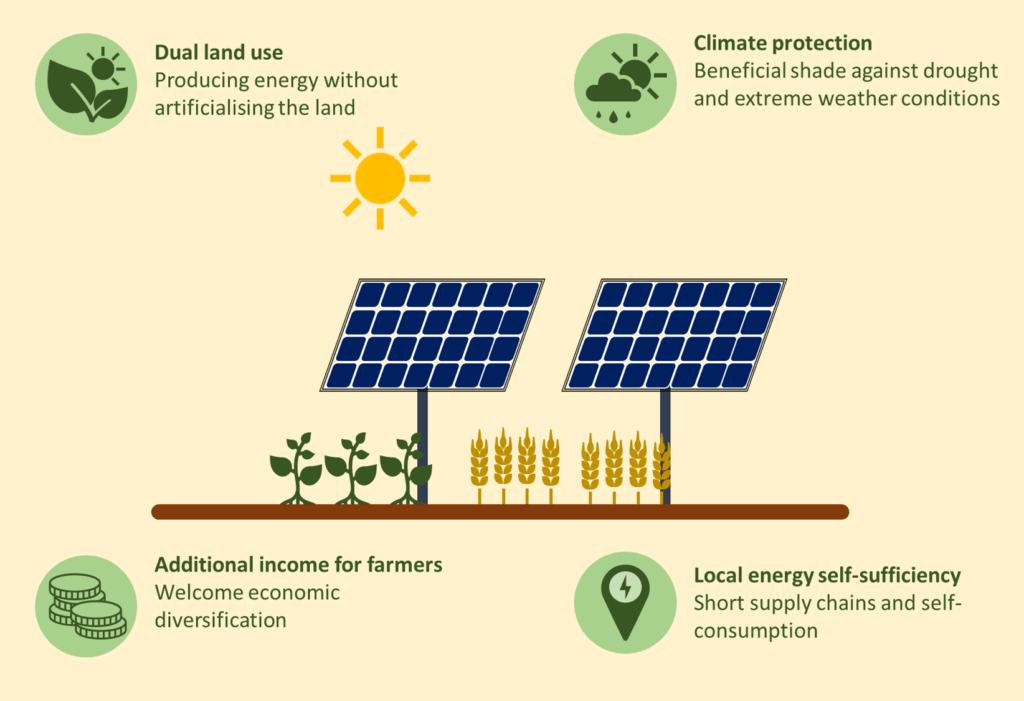

Agrivoltaics is an innovative solution that addresses agricultural, energy and climate issues. By enabling food production and renewable electricity generation to coexist functionally, it offers a range of strategic advantages for rural areas and farms.

3.1 Optimising land use

In a context of increasing pressure on land, agrivoltaics allows agricultural land to be used for two purposes. Unlike conventional photovoltaic installations, which can lead to soil artificialisation, agrivoltaic systems maintain the agricultural use of plots while producing energy. This approach helps to limit competition between food and energy uses of the soil (INRAE, 2024).

According to Weselek et al. (2019), combining agricultural production and solar energy on the same plot can, under certain experimental conditions, improve overall land productivity by 10 to 70%, depending on the Land Equivalent Ratio (Weselek et al., 2019). These results vary greatly depending on the crops, climate and design of the installations.

The Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) compares the combined productivity (crop + electricity) of an agrivoltaic system with separate production. An LER > 1 indicates a gain in land efficiency, but its calculation must take into account the loss of non-cultivable area associated with the structures. (Mead & Willey, 1979)

3.2 Climate resilience and crop protection

Photovoltaic structures create partial shade that alters the local microclimate. Several studies have shown that this shade can reduce water stress on plants, protect against climatic hazards (frost, hail, heat waves), and improve the regularity of plant growth. In some German experiments, yields were higher under solar panels in dry years (e.g. +11% for potatoes and +3% for wheat in 2018 at the site studied), illustrating the variability depending on the year and crop; these results show a potential advantage in conditions of water stress, but they are not systematic. (Trommsdorff et al., 2021; Weselek et al., 2019)

In Weselek et al. (2019), the authors indicate that in arid climates or climates affected by climate change, the shade provided by solar panels can improve crop water productivity, in particular by reducing evapotranspiration and favourably modifying the local microclimate.

3.3 Diversification of agricultural income

Agrivoltaics offers farmers an additional source of income, either through the sale of electricity produced or through the leasing of land to energy operators. This economic diversification can strengthen the financial resilience of farms, particularly in sectors vulnerable to fluctuations in agricultural markets or climatic hazards (Jeanneton, 2020).

Weselek et al. (2019) also point out that agrivoltaic systems can increase the economic value of agriculture, while contributing to the decentralised electrification of rural areas, particularly in developing countries.

The energy produced can also be consumed locally, promoting short energy supply chains. This approach strengthens the energy autonomy of rural areas and reduces losses associated with electricity transmission.

3.4 Agronomic innovation and adaptation of practices

Agrivoltaic projects encourage a reconfiguration of agricultural practices. They often incorporate monitoring technologies (sensors, smart irrigation), crop rotations adapted to the level of shade, and agroecological systems. This dynamic promotes agronomic innovation and the adaptation of crops to new climatic constraints (Barron-Gafford et al., 2019).

3.5 Animal welfare and extensive livestock farming

In pastoral systems, solar panels can provide shade that is beneficial to animal welfare. In summer, this protection reduces heat stress on herds, improves their feeding behaviour and reduces heat-related health risks (INRAE, 2024).

3.6 Contribution to the energy transition

Agrivoltaics actively contributes to the decentralisation of energy production. By integrating photovoltaic capacity into rural areas, it contributes to national and European climate objectives, while strengthening local energy autonomy. It is part of regional energy mix and greenhouse gas emission reduction strategies (Carrausse, 2024).

4. Legislative framework in Belgium

The Belgian regulatory framework is still evolving, influenced by European guidelines on energy transition and the preservation of agricultural land. The development of agrivoltaics depends on each region, which develops its own regulatory criteria based on its territorial priorities and land use planning.

4.1 Wallonia

In Wallonia, the development of agrivoltaics is governed by the Territorial Development Code (CoDT), which requires that any installation in an agricultural area demonstrate its compatibility with a primary agricultural activity. This requirement aims to prevent the substitution of agricultural use with a purely speculative energy activity.

To date, the regulations are based on general texts, in particular the circular of 14 March 2024 on planning permission for photovoltaic installations. However, this circular is considered insufficient to regulate the specificities of agrivoltaics. The White Paper on Agrivoltaics in Wallonia (Edora, 2024) recommends replacing it with a dedicated government decree, which would define clear guidelines, precise agronomic and technical criteria, and the creation of an independent observatory responsible for monitoring projects. To date, no official timetable has been announced by the Walloon government regarding the adoption of such a decree.

Among the flagship initiatives, the Wierde (Namur) project combines a 10 MWp photovoltaic power plant covering 14 hectares with sheep farming and beekeeping activities, illustrating the functional coexistence of agricultural and energy production. Other experiments are underway, notably solar greenhouses in Ath, Gembloux and Chimay, integrating market gardening under photovoltaic roofing. (Renouvelle, 2024).

Despite these advances, the development of agrivoltaics in Wallonia remains limited, awaiting a more structured legal framework that guarantees agricultural priority, the economic viability of farmers, and the territorial coherence of projects.

4.2 Brussels

In the Brussels-Capital Region, agrivoltaic potential is constrained by the scarcity of agricultural land and high urban density. However, opportunities are emerging in the context of urban agriculture, notably through the installation of solar panels on the roofs of agricultural buildings, urban greenhouses, or vertical farms.

However, given the virtual absence of agricultural land in the Brussels Region, agrivoltaics remains limited to niches such as urban greenhouses or agricultural roofs.

The regional energy and climate strategy encourages photovoltaic self-consumption in peri-urban areas, in conjunction with food belt projects. Agrivoltaics is seen there as a technical complement to innovative agricultural models, but it is not yet subject to a specific regulatory framework. Projects are assessed on a case-by-case basis, according to general urban planning and building energy performance rules.

4.3 Flanders

In Flanders, agrivoltaics remains at an experimental stage, although interest in this approach is growing, particularly in the horticultural and market gardening sectors. Current regulations impose strict conditions on the preservation of agricultural land, in particular through the Beleidsplan Ruimte Vlaanderen (Department of Environment, 2018), which aims to limit land artificialisation and guarantee the primacy of agricultural use in rural areas.

To date, there is no specific legal framework governing agrivoltaics in Flanders. Projects must comply with general land use planning rules, environmental requirements, and standards relating to renewable energy production. The Flemish authorities are currently focusing on pilot projects, often carried out in partnership with research institutes such as ILVO, in order to assess the impact of photovoltaic structures on agricultural yields, soil quality, and local biodiversity.

In addition, the decree of 17 February 2023 requires the integration of photovoltaic panels for large electricity consumers, which could indirectly promote the emergence of agrivoltaic models in certain intensive farms. However, this obligation is part of a general energy policy and does not constitute a framework dedicated to agrivoltaics (Monard Law, 2023; Luminus, 2023; WeGreen, 2024).

4.4 Conclusion

The development of agrivoltaics in Belgium is hampered by a variety of regional regulatory frameworks, reflecting the specific priorities of each federated entity. Overall, in the face of the energy transition and growing concerns about land management, only Wallonia is moving towards a regulatory framework structured around agrivoltaics. Brussels and Flanders remain in a more experimental phase for the time being, lacking dedicated regulatory instruments, which could slow down the coordinated development of large-scale agrivoltaic projects. Institutional reinforcement, through the development of specific regional legal frameworks and support measures, appears necessary to ensure the territorial coherence and viability of these innovative projects.

5. Comparison with Europe

Agrivoltaism is developing at different rates across Europe, depending on the climatic, agricultural and regulatory contexts specific to each country. While Belgium is still in the structuring phase, some Member States have already put in place ambitious measures combining public support, legal frameworks and technical innovation.

France: regulatory structuring and growth

Since the APER law of 10 March 2023, France has put in place a specific legal framework for agrivoltaics. This was clarified by Decree No. 2024-318 of 8 April 2024, the order of 5 July 2024, and the ministerial instruction of 18 February 2025, which require, in particular, the maintenance of agricultural activity, the reversibility of installations and mandatory agronomic monitoring (Decree No. 2024-318, 2024; Ministry of Ecological Transition, 2024; Ministry of Ecological Transition, 2025). The work of the ADEME (2021) also serves as a technical reference for characterising projects.

According to projections, France could reach 2 GW of installed agrivoltaic power by 2026, despite persistent administrative complexities. In the field, companies such as Sun’Agri and Ombrea are experimenting with innovative systems such as raised panels, mobile structures and modular shading (Journal du Photovoltaïque, 2024).

Germany: integration into the EEG law and simplification of procedures

In Germany, agrivoltaics is explicitly recognised within the renewable energy support scheme. Since the revision of the EEG law, agri-PV has been eligible for tenders for ground-mounted installations, and no longer only for so-called ‘innovation’ tenders (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz, 2023). In 2023, the government also adopted Solarpaket I, which aims to speed up procedures and expand eligible areas (BMWK, 2023). At the same time, the DIN SPEC 91434 (2021) standard establishes minimum requirements for project planning and evaluation, ensuring that agricultural function remains a priority.

Italy: support from the PNRR and ramp-up

Italy has embarked on a proactive strategy with its National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR). The decree of 13 February 2024 introduced a specific incentive scheme for agrivoltaico innovativo projects, with a target of approximately 1.04 GW of new capacity (Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Sicurezza Energetica [MASE], 2024a). Detailed operating rules were published in the same year (MASE, 2024b). In June 2025, Italy extended the deadline for completion of PNRR projects to 30 June 2026 in order to ensure their implementation (MASE, 2025).

Spain: climate adaptation and local innovation

Spain does not yet have a specific national regulatory framework for agrivoltaics. Projects are being developed within the general framework of renewable energy and self-consumption (Real Decreto 244/2019, 2019). However, several pilot initiatives are emerging, such as the Winesolar project led by Iberdrola, which combines dynamic solar panels, smart irrigation and viticulture adapted to drought conditions (Iberdrola, 2022). These local experiments provide an interesting laboratory for adapting agrivoltaics to Mediterranean climates.

6. Criticism and controversy

Although agrivoltaics is gaining popularity as a hybrid solution to climate and energy challenges, it is not without its critics. These mainly focus on land speculation, ecological risks, regulatory complexity, and tensions between agricultural and energy stakeholders. Several citizen and agricultural organisations, such as Terre-en-vue, are warning of the potential pitfalls of poorly regulated development.

6.1 Risks of land speculation and land grabbing

One of the major complaints concerns the growing pressure on agricultural land. Some photovoltaic developers, sometimes backed by investment funds, seek to acquire or lease land on a long-term basis, to the detriment of local farmers. This dynamic can lead to a form of disguised land grabbing, or even agricultural abandonment, if the projects do not guarantee significant agricultural activity (Terre-en-vue, 2023).

In Wallonia, citizen cooperatives have denounced cases where land has been taken out of agricultural use for predominantly speculative energy projects, without any real consultation with the farmers concerned.

6.2 Impact on agricultural yields

The agronomic performance of agrivoltaic systems depends heavily on the design of the installations: panel height, orientation, density, type of crop. An ill-suited design can lead to a reduction in agricultural yields, particularly due to excessive shading or interference with farming practices (Marrou et al., 2013). Conversely, some well-designed models can improve water productivity and protect crops from climatic hazards.

6.3 Risks to biodiversity and soils

The ecological effects of agrivoltaic installations vary depending on maintenance practices and project planning. Excessive artificialisation, soil compaction or habitat fragmentation can harm local biodiversity. Conversely, projects that incorporate flowering meadows, honey hedges or refuge areas can promote beneficial wildlife and pollinators (HAL, 2020).

The lack of post-installation ecological monitoring is often cited as a weakness of current projects, particularly in the absence of an independent observatory.

6.4 Social acceptability and land use conflicts

Agrivoltaics is causing growing tensions between agricultural and energy stakeholders and citizens. Some farmers complain of a loss of control over their land, while local residents are concerned about the impact on the landscape or the privatisation of rural areas. Conflicts of use are emerging, particularly when projects are led by operators from outside the area, without local consultation (Terre-en-vue, 2023; Revue générale du droit, 2025).

In France, too, ADEME and several associations also highlight the risk of greenwashing, when certain projects are presented as ‘agrivoltaic’ when in reality agricultural activity is secondary or marginal.

The issue of social acceptability is becoming central, and several experts are calling for shared governance of projects, including farmers, local authorities and citizens.

6.5 Case study: Terre-en-vue’s position

The organisation Terre-en-vue, active in Wallonia, openly criticises certain projects that it considers too speculative or disconnected from agricultural realities. It advocates for a clear legal framework, priority given to agricultural use, and direct involvement of farmers in project governance. It also proposes alternative models based on collective land ownership and co-construction of facilities (Terre-en-vue, 2023).

6.6 Advantages and risks of agrivoltaics

7. Avenues for controlled development

Faced with the risks of abuse identified by actors such as Terre-en-vue — land speculation, loss of agricultural control, soil artificialisation — several levers can be mobilised to ensure the balanced, transparent and sustainable development of agrivoltaics. These avenues aim to strengthen local governance, secure farmers’ rights and promote a citizen-led energy transition.

7.1 Involving citizen cooperatives: towards local and shared governance

The controlled development of agrivoltaics requires the active involvement of local stakeholders, particularly citizen cooperatives engaged in renewable energy production.

In Belgium, cooperative structures bring together more than 23,000 cooperative members and collectively manage more than 100 MW of installed capacity in wind, photovoltaic, hydroelectricity and biomass.

These cooperatives are not yet directly involved in large-scale agrivoltaic projects, but their model offers powerful levers to respond to the criticisms raised by organisations such as Terre-en-vue:

- They promote collective and local ownership of energy infrastructure, reducing the risk of land speculation.

- They enable fair distribution of profits by involving farmers, citizens and communities in governance.

- They ensure financial transparency and traceability of contractual commitments, strengthening trust between stakeholders.

This cooperative model can be adapted to agrivoltaics in rural areas by involving farmers from the design phase onwards, guaranteeing their decision-making role and avoiding the extractive approaches denounced in certain projects. It constitutes a credible alternative to arrangements dominated by private operators from outside the territory.

7.2 Providing security for farmers through a clear contractual framework

A robust legal and contractual framework is essential to protect farmers from the risks of displacement or dependency. It must include:

- Priority given to agricultural activity throughout the duration of the project.

- Decommissioning clauses at the end of the project’s life, with an obligation to restore the land.

- Fair revenue sharing between developers, farmers and cooperatives.

- Guarantees of reversibility and non-substitution of agricultural use.

These elements are recommended by the White Paper on Agri-voltaics and supported by actors such as Renouvelle (2024), which advocate for transparent and balanced contractualisation.

7.3 Designing suitable and environmentally responsible installations

The technical design of installations must be tailored to local crops, climate and agricultural practices. This implies:

- A controlled shading rate to avoid yield losses.

- Flexible or mobile structures allowing for seasonal adaptation.

- Regular agronomic and ecological monitoring, including indicators of biodiversity, soil quality and productivity.

A scientific summary published on HAL (2020) shows that the impacts on soil and biodiversity can be positive or neutral, provided that projects are well planned and maintained.

7.4 Create an independent observatory

To ensure transparency and continuous improvement, the White Paper recommends the establishment of an independent observatory responsible for:

- Evaluating the agricultural and energy performance of projects.

- Disseminating good practices and feedback.

- Ensuring post-permit monitoring and traceability of contractual commitments.

This tool would help to strengthen trust between stakeholders and prevent the abuses identified by Terre-en-vue.

8. Conclusion

Agrivoltaism represents a strategic opportunity for Belgium, at the crossroads of two major imperatives: the energy transition and the preservation of agricultural land. By combining food production and solar production on the same surface area, this approach offers potential for territorial synergy, capable of meeting climate objectives while strengthening the resilience of the agricultural sector.

In the country’s three regions, the dynamics are contrasting but convergent:

- In Wallonia, the regulatory framework is currently being structured, with clear recommendations to guarantee agricultural priority and provide a framework for projects.

- In Flanders, projects remain experimental, but are part of a strategy to preserve land and promote technical innovation, particularly in the horticultural sector.

- In Brussels, the potential is more limited, but urban agriculture and agricultural rooftops offer interesting prospects for local self-consumption.

However, the development of agrivoltaics in Belgium cannot be left to market forces alone. It must be framed by coherent public policies based on the principles of land justice, shared governance and environmental transparency. The risks identified – speculation, agricultural abandonment, conflicts of use – require strong guarantees at the legal and territorial levels.

For agrivoltaics to become a sustainable lever for Belgium’s energy transition, several conditions must be met:

- A harmonised legal framework, adapted to regional specificities, but based on common criteria of agricultural compatibility, reversibility of installations and fair contracting.

- Local and citizen-led governance, involving farmers, local authorities and energy cooperatives in the design and management of projects.

- Independent environmental monitoring, via a national or interregional observatory responsible for assessing agronomic, ecological and social impacts.

- Enhanced applied research, to adapt technical configurations to Belgian soil and climate conditions and maximise cross-benefits.

Finally, the role of citizen cooperatives in the energy transition deserves to be fully explored. Although still little present in agrivoltaics, they offer a model of transparent, local and inclusive governance, capable of responding to criticism from stakeholders in the agricultural world and strengthening the social acceptability of projects.

Agrivoltaics should not be a substitute solution, but an intelligent complement to the development of photovoltaics on artificial surfaces. If it is well designed, well supervised and well governed, it can become a structural pillar for a more resilient, more sober and more united Belgium.

9. Energiris’ point of view: towards a citizen-led and regional energy transition

In view of the issues identified above (land governance, social acceptability, balance between agricultural and energy uses) it seems relevant to examine the potential contributions of citizen cooperatives in the deployment of ethical and locally-based agrivoltaic projects.

These structures, based on the active participation of citizens, offer shared governance models that can contribute to better territorial ownership of energy production. By involving local residents from the design phase onwards, they promote transparency, traceability of benefits and equitable distribution of economic returns.

Several cooperatives active in the field of renewable energy in Belgium are experimenting with collaborative arrangements, particularly in urban and semi-urban contexts. Although these initiatives are still rare in the agricultural sector, their transposition to agrivoltaic projects seems feasible, in partnership with farmers or citizen-led land structures such as Terre-en-vue.

This type of arrangement would make it possible to guarantee priority for agricultural use, prevent the risks of land speculation, and strengthen short energy circuits through local self-consumption. It is part of a fair transition approach, where climate imperatives do not take precedence over the food and social functions of the land.

By bringing together farmers, citizens and local authorities around jointly developed projects, citizen cooperatives are laying the foundations for a solidarity-based, transparent and resilient agrivoltaic sector that is capable of reconciling energy sovereignty, land justice and agricultural vitality.

With this in mind, certain citizen cooperatives active in the field of renewable energy, such as Energiris, fully identify with this territorial and inclusive approach to agrivoltaics. They express their willingness to collaborate with agricultural and land stakeholders, particularly organisations such as Terre-en-vue, in order to co-develop projects that respect land use, local balances and the principles of shared governance.

Beyond my role at Energiris, I place great importance on sharing knowledge. I have always considered education to be an essential tool for helping everyone better understand energy issues and the concrete solutions available to us. Sharing what I discover and making complex topics accessible to others is also my way of contributing to a fairer, more inclusive transition.

References consulted in writing this article

- ADEME. (2021). Characterising photovoltaic projects on agricultural land and agrivoltaics. Agency for Ecological Transition.

- ADEME. (2021). Agrivoltaics: current situation and recommendations. Agency for Ecological Transition.

- ADEME. (2023). Agrivoltaism in France: current situation and recommendations. French Environment and Energy Management Agency.

- Agrinove. What should we think of agrivoltaism?: https://agrinove-technopole.com/2023/07/que-penser-agrivoltaisme/

- Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Protection (BMWK). (2023). Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG 2023).

- Department of Environment, (2018), Flanders Spatial Policy Plan: strategic vision. Vlaanderen.be. https://www.vlaanderen.be/bouwen-wonen-en-energie/bouwen-en-verbouwen/bouwvergunningen-en-plannen/ruimtelijke-ordening/beleidsplan-ruimte-vlaanderen

- Barron-Gafford, G. A., et al. (2019). Agrivoltaics provide mutual benefits across the food–energy–water nexus in drylands. Nature Sustainability, 2(9), 848–855., https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0364-5

- Carrausse, R. (2024). In the shadow of solar panels: agrivoltaics. A look back at a socio-technical trajectory of legitimisation. Sustainable development and territories, 15(3). https://journals.openedition.org/developpementdurable/24653

- Claude Grison, Lucie Cases, Maïlys Le Moigne, Martine Hossaert-Mckey. Photovoltaism, agriculture and ecology: from agrivoltaism to ecovoltaism. ISTE; Wiley, 156 p., 2021, Ecological sciences, Agathe Euzen; Dominique Joly, 978-1-78630-720-0. ⟨10.1002/9781119887720⟩. ⟨hal-04159278⟩

- DIN. (2021). DIN SPEC 91434: Agri-Photovoltaik – Anforderungen an die landwirtschaftliche Hauptnutzung. Deutsches Institut für Normung.

- Decree No. 2024-318 of 8 April 2024 on agrivoltaic and photovoltaic installations on agricultural, natural or forest land.

- Dupraz, C., et al. (2011). Combining solar panels and food crops for optimising land use: Towards new agrivoltaic schemes. Renewable Energy, 36(10), 2725–2732.

- Fraunhofer ISE. (2021). Agri-PV: Opportunities for Agriculture and the Energy Transition. Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems.

- HAL. (2020). Impact of agrivoltaics on soil and biodiversity. HAL open archives.

- Iberdrola. (2022). Winesolar: Pilot agrivoltaic project in vineyards.

- INRAE. (2024). Agri-voltaics, the way forward. Bioeconomy dossier. https://www.inrae.fr/dossiers/agriculture-forets-sources-denergie/lagrivoltaisme-voie-lavenir

- Jeanneton, M.-B. (2020). Combining electricity and food production on a single plot of land: agrivoltaics. Master’s thesis, University of Pau and Pays de l’Adour. https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-03330107

- Journal du Photovoltaïque. (2024). France-Germany: agrivoltaics compared. Excerpt from publication.

- Wallonia White Paper. (2024). White Paper – Agrivoltaism in Wallonia. Cluster Tweed. Available at: https://clusters.wallonie.be/tweed/sites/tweed/files/2024-07/Livre%20Blanc%20-%20Agrivoltai%CC%88sme%20en%20Wallonie.pdf

- Luminus. (2023, 27 March). Why is Flanders making photovoltaic panels mandatory for large electricity consumers? Lumiworld Business. https://lumiworld-business.luminus.be/fr/produire-sa-propre-energie/panneaux-solaires/pourquoi-la-flandre-rend-elle-les-panneaux-photovoltaiques-obligatoires-pour-les-gros-consommateurs-delectricite

- MASE. (2024a). Ministerial Decree of 13 February 2024: Incentives for innovative agrivoltaic systems. Ministry of the Environment and Energy Security.

- MASE. (2024b). Operating rules for access to innovative agrivoltaic incentives. Ministry of the Environment and Energy Security.

- MASE. (2025). Decree of 27 June 2025: Extension of PNRR terms for innovative agrivoltaic systems. Ministry of the Environment and Energy Security.

- Marine Blaise. Response of grassland to shading in agrivoltaic parks through simulation and experimentation. Environmental Sciences. 2023. hal-04191860, https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-04191860v1

- experimentation. Environmental Sciences. 2023. hal-04191860

- Marrou, H., et al. (2013). Microclimate under agrivoltaic systems: Is crop growth affected in the partial shade of solar panels? Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 177, 117–132.

- Mead R, Willey RW. The Concept of a ‘Land Equivalent Ratio’ and Advantages in Yields from Intercropping. Experimental Agriculture. 1980;16(3):217-228. doi:10.1017/S0014479700010978

- Ministry of Ecological Transition. (2024). Decree of 5 July 2024 on the conditions for installing photovoltaic facilities in agricultural areas.

- Ministry of Ecological Transition. (2025). Ministerial instruction of 18 February 2025 on agrivoltaics.

- Monard Law. (2023, 20 February). Flanders makes solar panels mandatory for large consumers from 2025. Monard Law. https://monardlaw.be/fr/histoires/informe/vlaanderen-verplicht-zonnepanelen-voor-grootverbruikers-vanaf-2025

- pv magazine. (2025, 14 May). Agrivoltaism is gaining momentum in Italy and France, according to two national associations. https://www.pv-magazine.fr/2025/05/14/lagrivoltaisme-entre-dans-le-vif-du-sujet-en-italie-et-en-france-selon-deux-associations-nationales/

- Royal Decree 244/2019, of 5 April, regulating the administrative, technical and economic conditions for self-consumption of electrical energy. Official State Gazette.

- Renouvelle. (2024). Agrivoltaism in Wallonia. Renouvelle.be.

- Renouvelle. Agrivoltaism: a challenge for the energy transition in Wallonia: https://www.renouvelle.be/fr/agrivoltaisme-un-enjeu-pour-la-transition-energetique-en-wallonie/

- Renouvelle. Namur: Belgium’s first agrivoltaic project will start producing energy before the end of the summer.: https://www.renouvelle.be/fr/namur-le-premier-projet-agrivoltaique-de-belgique-produira-avant-la-fin-de-lete/

- Schindele, S., Trommsdorff, M., Schlaak, A., Obergfell, T., Bopp, G., Reise, C., … & Högy, P. (2020). Implementation of agrophotovoltaics: Techno-economic analysis of the price-performance ratio and its policy implications. HAL. Available at: https://hal.science/hal-02877032v1

- Terre-en-vue. (2023). Agri-photovoltaic project: a false good idea? [Online]. Available at: https://terre-en-vue.be/actualite/article/projet-agri-photovoltaique-une-fausse-bonne-idee-qui-menace-le-foncier-agricole

- Terre-en-vue (December 2023). Photovoltaic panels: on what type of land? [Online]. Available at: https://terre-en-vue.be/presentation/plaidoyer/article/panneaux-photovoltaiques-oui-mais-sur-quel-sol

- Terre-en-vue et al. (2021). Ground-mounted photovoltaic energy, positioning [Online]. Available at: https://terre-en-vue.be/IMG/pdf/cer_ac_jd_210223_positionnement_pv_sur_sol.pdf

- Terre-en-vue. Agrivoltaic project in Jemelle: TAKE PART IN THE PUBLIC ENQUIRY! https://terre-en-vue.be/actualite/article/projet-d-agrivoltaisme-a-jemelle-participez-a-l-enquete-publique

- Trommsdorff, M., et al. (2021). Agrivoltaics: Synergies between agriculture and solar energy. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 140, 110694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110694

- WeGreen. (2024, 15 January). Obligation for companies in Flanders: solar panels from 2025. WeGreen. https://www.we-green.be/blog/obligation-pour-les-entreprises-en-flandre-panneaux-solaires-des-2025

- Weselek, A., et al. (2019). Agrophotovoltaic systems: applications, challenges, and opportunities. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 39, 35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-019-0581-3.

- https://www.inrae.fr/dossiers/agriculture-forets-sources-denergie/lagrivoltaisme-voie-lavenir

- https://www.inrae.fr/dossiers/agriculture-forets-sources-denergie/lagrivoltaisme-voie-lavenir

- https://www.lecho.be/entreprises/energie/agrivoltaisme-la-wallonie-a-l-heure-du-choix/10616323.html

[1] Accelerating Renewable Energy Production